By Mark Heming.

MiddleJanes

Mark Heming at MiddleJanes

Talk about a late-period artist. Mark Heming was already in his nineties the first and only time he ever exhibited his work, but since his death in 1999, he has slowly but surely found an audience; Julie Andrews and the artist Eric Fischl are both fans. Outside their private collections, though, his paintings got their first full-scale display thanks to MiddleJanes, which is run by Heming’s daughter Sarah, a former casting director who’s now dedicated herself to her father’s estate. Heming, a German Jew from the Upper East Side, painted portraits, and while he was struck by faces he’d see in places like the bread line during the Depression, he never reproduced them entirely faithfully; his paintings were instead amalgamations of people he’d see—and often stare too long at—around New York.

From Rough Draft to Exhibition: ‘Outsider’s’ Art Is (Finally) Revealed

By JAMES BARRON JAN. 15, 2017

Sarah Heming has assembled a collection of works by her father, Mark, that will be shown at the Outsider Art Fair. Nicole Bengiveno for The New York Times

“Typist wanted,” the classified ad said. This was in the 1940s, when college students like Mark Heming placed ads like that to turn the rough drafts of their term papers into something. The typist looked through the pages he handed her and asked: “Who are these faces?”The typist, Mary Jane Christenson, was captivated by the drawings in the margins, which were more than the doodles of a practiced procrastinator struggling to think of a compelling topic sentence. She thought they were portraits and quite good, and she said so. She also said, “You should be an artist.”And with that, she turned a rough draft of a man into something.But first she typed the term paper. Then she moved in with him. And, to skip several steps ahead, Mr. Heming’s work is about to be shown at the Outsider Art Fair, which opens on Thursday at the Metropolitan Pavilion in Chelsea, and runs through Sunday. (Sarah Heming, his daughter, will exhibit his work at a booth under her business name, MiddleJanes.)The fair traces “outsider art” to a manifesto by Jean Dubuffet that referred to art “produced by persons unscathed by artistic culture” whose work is derived “from their own depths, and not from the conventions of classical or fashionable art.” So everything on display in the 60 booths at the fair will be the work of artists like Mr. Heming who never took an art class.Ms. Heming, a former casting director who has become her father’s champion, said the outsider fair was an appropriate setting for his first full-scale showing because he was an outsider in the world, and in the art world. He showed his works only once — and then it was only three paintings, when he was past 90. When he was younger, he shied away from anything that would have made him a part of the conversation as stars of his generation like Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning were catching on.Mr. Heming, who died in 1999, had a style that was very much his own. And to look at his paintings now is to discover a link to another time, and another New York. “Like ‘Time and Again,’ but that was a book,” said Ms. Heming. Here she was referring to the Jack Finney novel about time travel to 19th-century Manhattan, which the writer Tony Hiss called “the classic book about not letting go of an old city.”

A family photograph of Mr. Heming and his father. Nicole Bengiveno for The New York Times

Listening to Ms. Heming tell her father’s story was like time-traveling into a privileged corner of that old city. She said he was delivered — at home, on the Upper East Side, in 1907 — by Dr. Leopold Stieglitz, respected then as a carriage-trade physician, remembered now as a brother of the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Mark Heming’s father ran an advertising agency that handled The New York World, Joseph Pulitzer’s newspaper. His mother’s family owned the brewery in Brooklyn that made Rheingold beer.He was not particularly nostalgic, but he had his memories. “Sometimes he would talk about how the trolley driver would let him drive the trolley” on the line that ran across town, through Central Park, she said, “and he remembered Fifth Avenue with empty lots, and the Fire Department flooded them. They played ice hockey.” He also remembered cutting school one afternoon to hear George Gershwin play “Rhapsody in Blue” — not just at any concert, but at the premiere, in February 1924, a few weeks after Mr. Heming turned 17.But the good memories were offset by an uneasiness about not quite belonging to the world into which he had been born. “My father felt like the black sheep — misunderstood, going to college but dropping out, drifting, dreading being called into his father’s office and asked, ‘What are you doing with your life?’” Ms. Heming said.He tried psychoanalysis. A psychoanalyst who had studied with Freud told him to move to Europe, advice Mr. Heming did not follow.“He drifted around in his 30s,” Ms. Heming said, working for a while at the department store Abraham & Straus.In his 40s, he tried school again, enrolling at the New School and placing the classified ad.“Two girls from Detroit who had just moved to New York, literally like a month before, answered the ad,” Ms. Heming said, “and one says, ‘This job sounds like too much work, and you’re a better typist.’” With that, she passed the telephone to her roommate, Miss Christenson.“She liked his voice,” Ms. Heming said, and she went to see how much work the term paper involved.

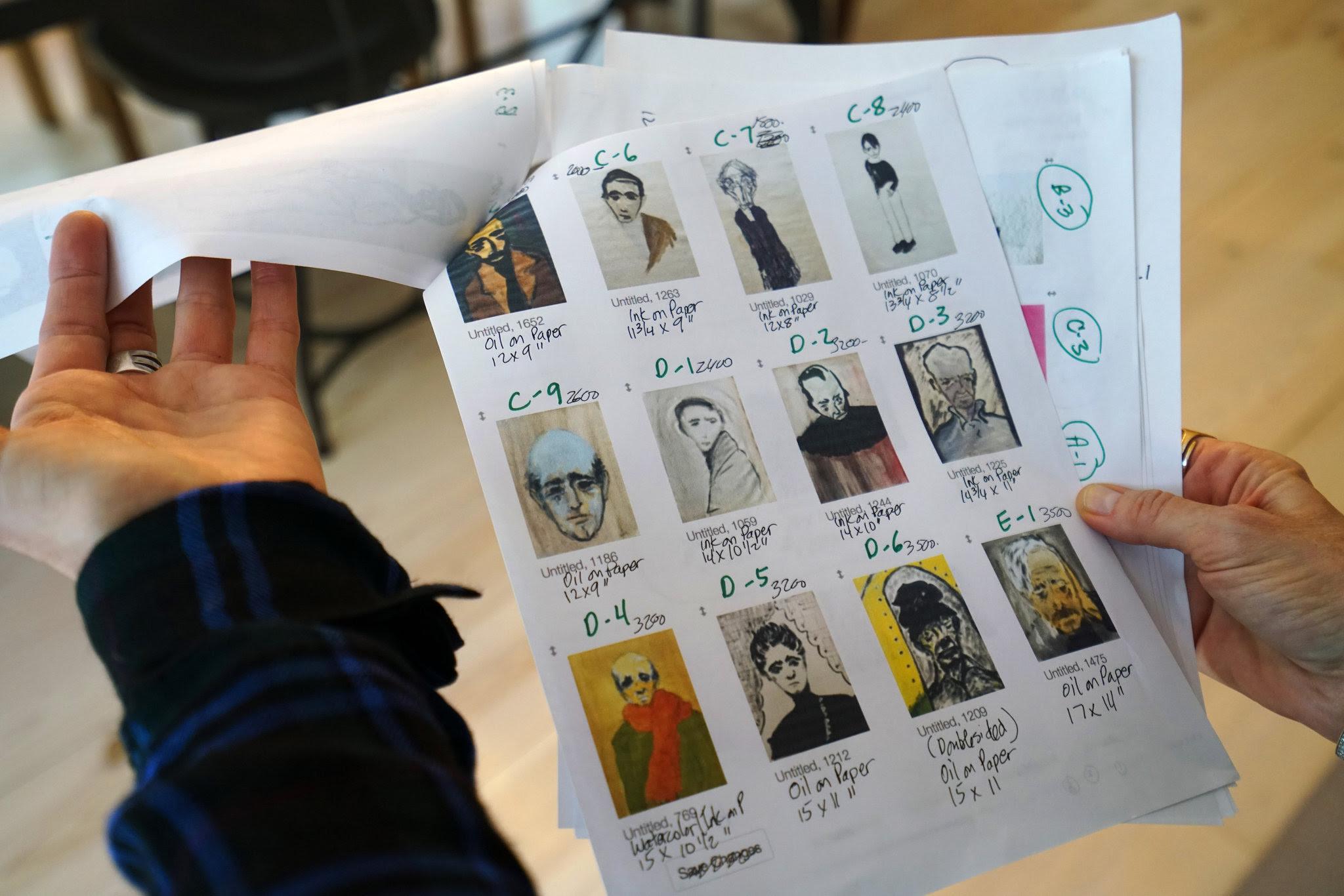

A worksheet of the portraits by Mr. Heming that will be on display. Nicole Bengiveno for The New York Times

“He shows her the notes he wants typed,” Ms. Heming said, “and there are all these faces in the margins.” She wanted to know whose faces they were.“They’re from my imagination,” he told her.It turned out that he could memorize a face he noticed walking down the street or sitting on the subway. Sometimes, to fix the details in his mind, he stared long enough, closely enough, to give someone the jitters. “His whole life he was being admonished not to stare at people — by his mother or by me, sometimes,” Ms. Heming said.In his studio, he reassembled the faces, but they were composites, some from yesterday, some from yesteryear. “I remember him saying he was very affected by faces in bread lines,” Ms. Heming said.In the 1950s, he wrote to the Guggenheim Museum. Ms. Heming said the reply amounted to “this is interesting — let us know what else you’re doing.” She said there were other rejections, and they might have contributed to his decision to leave Manhattan for eastern Long Island (and a house that was later sold to Christie Brinkley).So for years the only people who saw his work were Ms. Heming and her mother, the former Miss Christenson — and Ms. Heming’s daughter, Maisie, after she was born in 1997. “The faces were like members of the family,” Ms. Heming said, adding that as a child, Maisie talked to them.After Mr. Heming’s death, Ms. Heming arranged for an inventory of the paintings he left behind, and later, in a grocery store, a friend of hers bumped into a friend of his, the artist Eric Fischl. The friend sent Mr. Fischl a link to a website Ms. Heming had set up.“I frankly was not expecting anything — a Sunday painter at best, or a kind of primitive artist that was not particularly my forte or my taste even,” Mr. Fischl said. “What I saw was the real thing. This was an artist who was very able to communicate very authentic emotion, has a very deft expressionistic hand. He has this confident, intuitive sense of what is enough to capture the expression. Those qualities are not the qualities of a Sunday painter, they are the qualities of a real artist.”